A New York City fixture for “the best, the only, and the unexpected” for more than 170 years, Hammacher Schlemmer has decided not to renew the lease on its landmark E57th Street store, closing the chapter on the brand’s brick-and-mortar legacy.

Hammacher Schlemmer's flagship E57th Street store in 1926. Photo: Hammacher Schlemmer website

Hammacher Schlemmer’s retail space officially closed in February — just shy of a century in the building at 147 E57th Street. Originally opened on the Bowery in 1848 and moved uptown in 1926, Hammacher Schlemmer was one of the original “catch-all” stores where one could expect to find everything from a seven-person tricycle to a pop-up toaster (Hammacher Schlemmer was the first to sell one!).

“It’s certainly the end of an era, or at least a pause,” Hammacher’s VP of Marketing Ann Marie Resnick told Manhattan Sideways. “With 175 years in New York — almost the last 100 at our 57th Street location — we’ve served our customers through the Civil War, the Great Depression, two World Wars, the Apollo missions to the moon and the 9/11 terrorist attack. While the products we’ve offered over this time have evolved to keep up with our customers’ changing needs, our dedication to providing outstanding customer service is just as big a reason for our longevity. Ultimately, our decision to close our retail location is another response to a shift in our customers’ needs, as we found during the pandemic when people became much more comfortable ordering online.”

The department store was innovative in more ways than one. While the catalog branch of the brand is still America’s longest-running, Hammacher Schlemmer was also one of New York City’s first stores to have electric lights in its showroom and to install a telephone in its store. Hammacher is also known for its “rather unusual” lifetime product guarantee in which it offered customers a full refund as long as the product was operated for “standard non commercial use.” This guarantee, a Chicago Magazine article noted, was put to the test when a Hammacher Schlemmer customer returned his $400 Roomba vacuum after it tracked his dog’s excrement all over the house.

The Chicago Magazine article also highlights one of Hammacher’s quirkier long-standing traditions: a lack of brand names or product logos in its catalogs. Director of merchandising Stephen Farrell explained that the strategy, while initially designed to steer the customer towards the highest quality product over brand loyalty, had evolved into a defense mechanism against consumers looking to replicate the products more cheaply on Amazon.

Hammacher Schlemmer's E57th Street store in recent years.

But decades before e-commerce, there was the New York City flagship store. Opened in 1898 as a hardware store specializing in hard-to-find tools by proprietor Charles Tollner, it quickly gained a reputation as “the place to go when an item simply could not be found anywhere else.” Tollner was known for his thorough business mentorship to employees — among them, a young German immigrant named William Schlemmer, employed by Tollner for a generous $2 a week in 1853.

In 1857, Tollner decided to expand the operation, partnering with businessman Albert Hammacher to open a larger retail space renamed Hammacher & Tollner on the Bowery. The store’s hardware tools were an essential supplier for Northern manufacturers throughout the Civil War and business continued to grow. William Schlemmer, still an employee, began to buy out Charles Tollner’s stake in the brand, and when Tollner passed away in 1867 Schlemmer entered a partnership with Hammacher.

In 1881, the team published its first catalog — “six years before Sears and Roebuck”. In 1883, William Schlemmer became a full partner in the business and the store was renamed Hammacher Schlemmer & Co. Schlemmer’s son, William F Schlemmer, at this point active in the business for several years, joined his father in taking over operations after Albert Hammacher resigned in 1892.

Albert Hammacher and William Schlemmer. Photo: Hammacher Schlemmer Website

As the city moved into the 20th century, Hammacher Schlemmer maintained its position as a cutting-edge retailer, incorporating a new Auto Parts department and purchasing its own automobile for a new home delivery parcel service that predates Amazon Prime by nearly a century. The store also moved uptown to 13th Street and 4th Avenue — remaining there after the deaths of Albert Hammacher and William Schlemmer Senior and through World War I, during which the company was awarded a citation from the War Department of the United States for “distinguished service the loyalty, energy and efficiency in the performance of the war work by which Hammacher Schlemmer Co. added materially in obtaining victory for the arms of the United States of America in the war with the Imperial German Government and the Imperial and Royal Austro-Hungarian Government.”

In 1926, the company relocated to its landmark space on E57th Street in a 12-story building designed specifically for Hammacher Schlemmer’s merchandise. The Hammacher Schlemmer shopping experience gained such notoriety as to inspire a Broadway song by composer Howard Dietz entitled Hammacher Schlemmer, I Love You, and further made history in 1934 when they hired their first female salesperson.

When World War II broke out, Hammacher protested the Nazis by boycotting German products until armistice. In 1945, William F Schlemmer passed away at just 67, leaving his wife Else to run the company. In 1955, Else died — but not before leaving $473,000 (the equivalent of $5.3 million in today’s currency) to her employees.

Else Schlemmer at the store's 100th birthday celebration. Photo: Hammacher Schlemmer website

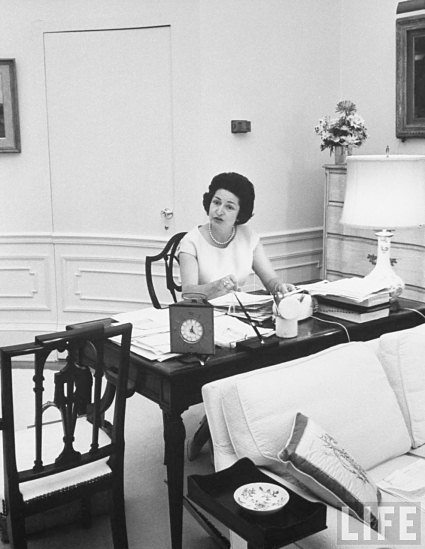

The latter half of the 20th century brought more prosperity for Hammacher Schlemmer — from retaining clientele like First Lady Claudia “Ladybird” Johnson, who hired the company to redecorate the White House closets, to carrying the first answering machine and microwave oven in 1968.

“Our employees treasured the personal relationships they cultivated with our customers over the years,” said Ann Marie Resnick. “Many times they would phone a customer when something new arrived in the store that they thought would be of interest to them. They also enjoyed assisting the occasional celebrity who would shop at the store, though they could sometimes be challenging. The staff welcomed the opportunity to assist any customer who shopped at Hammacher Schlemmer.”

The store’s commitment to “the best, the only, and the unexpected” reached new levels in 1983 when CEO J Roderick MacArthur founded the Hammacher Schlemmer Institute, a lab dedicated to quality test and rate consumer products. Three years later, the retailer became one of the first department stores to build an online outpost, while maintaining stores in Chicago, Beverly Hills and New York.

First Lady and Hammacher client Claudia "Lady Bird" Johnson at the White House. Photo: Hammacher Schlemmer website.

But the first years of the e-commerce boom would have its own effect on the retailer. In 2005, Hammacher Schlemmer closed its Chicago and Beverly Hills stores, although the New York flagship remained strong. In 2013, the Midtown space even got a makeover to further showcase its unique merchandise, including displays for a submarine and hovercraft. Hammacher Schlemmer managed to survive through the COVID-19 pandemic — pivoting to offer masks, sanitizing products and air purifiers — but three years later, the closure of its most well-known landmark marked the end of one of the city’s oldest department stores.

The brand lives on and continues to break barriers, existing as an entirely employee owned company, but its long legacy as a store where you could find almost anything has ended. “There will never be another store like Hammacher Schlemmer,” said Ann Marie. “It was the one place where consumers could come to get a glimpse into the not-to-distant future, with a touch of the outlandish and whimsical.”